The Acadians are Caught Between the Conflicts of France and Britain Leading to the French and Indian War

|

|

Fort Beauséjour Falls to British Troups

|

||||||

Contents

1) The Unofficial Commencement of the French-Indian Wars and The Acadian Exile - Le Grand Dérangement "Great Expulsion"

2) l'Acadie Caught Between the Conflicts of Two Colonial Empires - France and Britain

3) The fourth and final French and Indian War

4) Acadians found at Fort Beauséjour when it Capitulated to the British

5) Governor Charles Lawrence's Carpe Diem: Die is Cast for Acadian Ethnic Cleansing

6) Description from "Société Promotion Grand-Pré": the Grand-Pré National Historic Site of Canada Website

The Unofficial Commencement of the French-Indian Wars and The Acadian Exile - Le Grand Dérangement "Great Expulsion"

The French and Indian conflicts with Great Britain were the result of a decades long territorial dispute over the Ohio Valley region and the Canadian areas of empirical claims.

As France and Britain historically struggled for power in the Americas, l'Acadie became caught in the struggles for the reigns of power between the 2 empires.

The French and Indian conflicts with Great Britain were the result of a decades long territorial dispute over the Ohio Valley region and the Canadian areas of empirical claims. Ohio was important for a couple of reasons: firstly, it was a productive area for the fur trade; and secondly, the Thirteen Colonies (especially Virginia) wanted to expand westward and the French were in the way. The Americans were particularly unhappy that the French constructed Fort Duquesne in the area of contention. In 1753, the governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, sent an officer named George Washington to deliver a message ordering the French to leave. The French literally laughed in Washington's face.

"French and Indian" was a term designated by the British as the "opposition forces" that they confronted for empire expansion.Unlike the British, the French maintained relatively great relations with the Native Indian Tribes of Canada, including the Mi'kmaq Indians for certain reasons:

- The Thirteen Colonies often fought with one another and were by no means united.

- Indigenous peoples were suspicious of the Americans because they wanted to both trade with Indians and settle Indian lands.

- Indian peoples found the French more tolerable because Canadiens stressed trade as opposed to settlement.

- Consequently, the French were in a better position to construct a network of forts in North America's interior that effectively blocked the English-Americans.

- "Mido-chlorian Theory", i.e. The force was stronger with the French because they were born with more mido-chlorians than the English.

|

|

|

|

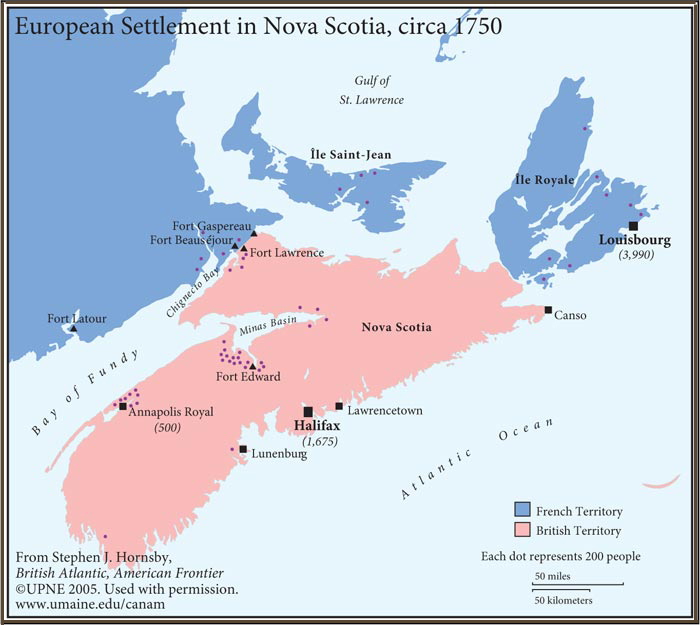

Click Here for Full Size Image |

||

In Acadia (Nova Scotia) in late August and early September, 1755, the Neutral French Inhabitants of Acadia were immediately declared "non-citizens" and their land/livestock were confiscated. There was some confusion and anger among the French. However, the British were prepared. Lt. Col. John Winslow rounded up and imprisoned 2,000 Acadians. To escape expulsion some Acadians fled into the forests where they were hunted down by British troops. Many French managed to avoid capture and made it to Quebec. Nevertheless, by the end of the first year alone nearly 7,000 French had been successfully exiled to prison and concentration camps in the Thirteen Colonies, Englad and France.

Although many Acadians were able to find refuge in Louisiana, the majority of Acadians migrated to Louisiana between the years, 1764 and 1770 with the last great migration being implemented by the Spanish Transport Ships of 1785 which transported Acadians who had been relocated to areas in and around Poitou France during the Great Expulsion years occurring between 1755 - 1762.

A doctor by the name of John Thomas, serving under Lt. Col. John Winslow, kept a detailed journal of the events in Acadia: “September 2nd. Pleasant day. Major Frye sent Lieutenant John Indocott’s detachment to the shore, with orders to burn the village at a place called Peteojack. September 18. Very strong gusts of wind, with rain and snow. Major Prible returned from an expedition with his men, who had burned 200 houses and barns. November 19th. Cold. We rounded up 230 head of cattle, 40 sows, 20 sheep and 20 horses and we came back. We have started moving the inhabitants out. The women were very distressed, carrying their newborns in their arms; others brought along in carts their infirm parents and their personal effects. In short, it was a scene in which confusion was mixed with despair and desolation.

The majority of Acadians were deported to New England, where they were not welcome: “The French neutrals arouse the general discontentment of the population, because they are papist zealots, lazy and of a quarrelsome mind,” declared the governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, who probably never met a French person in his life. He continued, “We have very few Catholics here, which makes the population very anxious for its religious principles and makes it fear that the French shall corrupt our Negroes."

|

|

|

The ships transporting the Acadians were overcrowded as the French were squished into holds to the point of suffocation. These transports were little more than prison ships. Some of the Acadians ended up in England and France, some in the Caribbean (Antilles), a scattered few in the English Colonies, and a number of them settled in Louisiana.

In 1758, the English captured Louisbourg and a final series of deportations began. The most infamous of all the persecuting British officers was Robert Monckton. Those French who resisted deportation (and weren't executed outright) were sent on an all expenses paid vacation to England where they labored for years in concentration camps. After their stay in England was over, the French were sent to France where they felt and were treated like foreigners.

When the expulsion finally ended in 1762, over 10,000 people had been removed; and of those 3,000 had died due to shipwrecks and disease. In 1764, the deportations officially came to an end and the ban on Acadians was lifted. The ban was lifted only because New France had been conquered and was no longer a threat. Approximately 3,000 people returned to Nova Scotia to start over again. However, many of the French returned only to find their farms occupied by English settlers. Consequently, the majority of these people migrated north-west to found settlements in present day New Brunswick.

l'Acadie Caught Between the Conflicts of Two Colonial Empires - France and Britain

The Bounce: Back and Forth - l'Acadie Becomes Pawn on the Empire Struggle Chess Board

As France and Britain historically struggled for power in the Americas, l'Acadie became caught in the stuggles for the reigns of power between the 2 empires.

There were several wars between the two empires in the years preceding the French-Indian War (also known as "The Seven Years War") –

| Years of War | North American War | European War | Treaty |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1689 – 1697 |

King William's War |

War of the Grand Alliance War of the League of Augsburg |

Treaty of Ryswick |

| 1702 – 1713 |

Queen Anne's War |

War of the Spanish Succession | Treaty of Utrecht (1713) - France cedes Newfoundland and Nova Scotia to Britain. |

| 1724 – 1725 | Dummer's War | Dummer's Treaty of December 15, 1725 | |

| 1744 – 1748 |

King George's War |

War of Jenkins' Ear War of the Austrian Succession |

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) - England gave Louisbourg back to the French - British colonists were furious & felt vulnerable from the North. |

| 1754 – 1763 |

The French and Indian War |

Seven Years' War | Treaty of Paris (1763) |

The above information and chart can be referenced at The French and Indian Wars Wikipedia page.

The fourth and final French and Indian War

Following King George’s War (1740-1748), French authorities in North America began to establish a line of forts in the American Ohio country west of the Allegheny Mountains. Their intent was to keep fur-trapping and trading activities in the hands of French citizens and to deny the area to land-hungry American colonists.

In the 1740s a group of Virginians received from the Crown a massive land grant for lands in the Ohio valley. The subsequent Ohio Company was established for the purpose of investing in western lands and, secondarily, for engaging in the fur trade. Tensions between the contending powers of France and England mounted rapidly.

The picture was further complicated by the allegiances of the area’s natives. As a rule, most of the tribes tended to favour the French who enjoyed a reputation for conducting business more fairly than the British. Further, the French trappers and traders did not threaten to inundate the region with settlers, unlike the British colonists.

Acadians found at Fort Beauséjour when it Capitulated to the British

As tensions built throughout 1754-55, leading to The French and Indian War, the British maintained a strategy to confront and deal with French "encroachments" along disputed lines of territory. A territorial dispute arose in April of 1755 at the Missaguash River which flows north of Nova Scotia and south of New Brunswick on the Isthmus of Chignecto, thereby forming a natural boundary. An Acadian settlement was formed on the territory there in 1672. Through their ingenious system of dykes, the Acadians reclaimed part of the marshland there to form a farming land of maximum fertility which yielded rich yearly harvests. The Acadian community was still flourishing there at the time of the French and British dispute for control of the nearby area.

|

Illustration: Fort Beauséjour & Fort Lawrence |

|

| Click here for a full size image | ||

In early June, 1755 a substantial force of approximately two hundred and seventy British regular troops and two thousand New England militia enlisted by Massachusetts Governor William Shirley landed at Fort Lawrence under the commands of Lieutenant Colonel Robert Monckton. The fleet landing took place directly across the Missaguash River from, and well within sight of, Fort Beauséjour. The French commander of Fort Beauséjour at this time, Louis Du Pont Duchambon de Vergor, had been informed of an approaching British fleet of ships prior to the landing and immediately sent word to Louisburg requesting reinforcements. After the fleet landing, de Vergor began hastily making fortifications for protection of Fort Beauséjour with the now apparant British threat that had positioned itself across the river.

One of de Vergor's preparations included Acadians from the community settled at the river. Well fortified with provisions, ammunition and weapons, Fort Beauséjour's defenses were limited by manpower with somewhere between one hundred and fifty and one hundred and ninety French soldiers and Canadian militia based there. De Vergor hurridly organized approximately two hundred Mi'kmaq Indians and ordered that the neighboring Acadians draw arms and report to Fort Beauséjour at once to assist in the defense of the fort. De Vergor's order was issued to the Acadians with the penalty of refusal or deserting the fort being one of death. Even so, many of the Acadians refused to take up arms against the British and fled. De Vergor ordered lock down into the fort and the surrounding structures to be burned to prevent the British troups from having luxury of cover.

The mounting conflict and British siege lasted only a short time. After securing strategic positions around Fort Beauséjour on Friday the 13th, British bombardment of the fort began on Saturday the 14th of June. On that day de Vergor received word from Louisburg that due to the position of the English forces no help was possible. On Sunday morning de Vergor decided to request a truce from Monckton which later resulted in Monckton's receiving of capitulation of de Vergor and his forces. Under the terms of capitulation agreed upon, Monckton, pending word from Halifax, pardoned the Acadians due to being pressed to bear arms by de Vergor and allowed the French troups an honorable exit and march to Louisburg.

The terms of surrender agreed on were as follows :

1. The commandant, officers, staff and others, employed for the king, and the garrison of Beausejour, shall go out with arms and baggage, drums beating.

2. The garrison shall be sent direct by sea to Louisbourg, at the expense of the king of Great Britain.

3. The garrison shall have provisions sufficient to last until they get to Louisbourg.

4. As to the Acadians,— as they were forced to bear arms under pain of death, — they shall be pardoned.

5. The garrison shall not bear arms in America for the space of six months.

6. The foregoing terms are granted on condition that the garrison shall surrender to the troops of Great Britain by 7, p. M., this afternoon.

(Signed) Robert Monckton.

At the camp before Beausejour, 16 June, 1755.

source: A HISTORY OF NOVA-SCOTIA OR ACADIE; BEAMISH MURDOCH, Esq., Q. C; VOL. II; HALIFAX, N. S.: JAMES BARNES, PRINTER AND PUBLISHER, 1866.; Microfiche. Ottawa : Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions, 1983. 7 microfiches (343 fr.) ; 11 x 15 cm. (CIHM/ICMH Microfiche series = CIHM/ICMH collection de microfiches ; no. 37227); Reproduction of original in: National Library of Canada

Fort Beauséjour was renamed Fort Cumberland almost immediately after its occupation by the British.

Another French garrison, Fort Gaspereau fell the day after Beauséjour and was occupied by a battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Winslow, who later was assigned the duty of deporting the Acadians. Fort Gaspereau was renamed Fort Monckton.

|

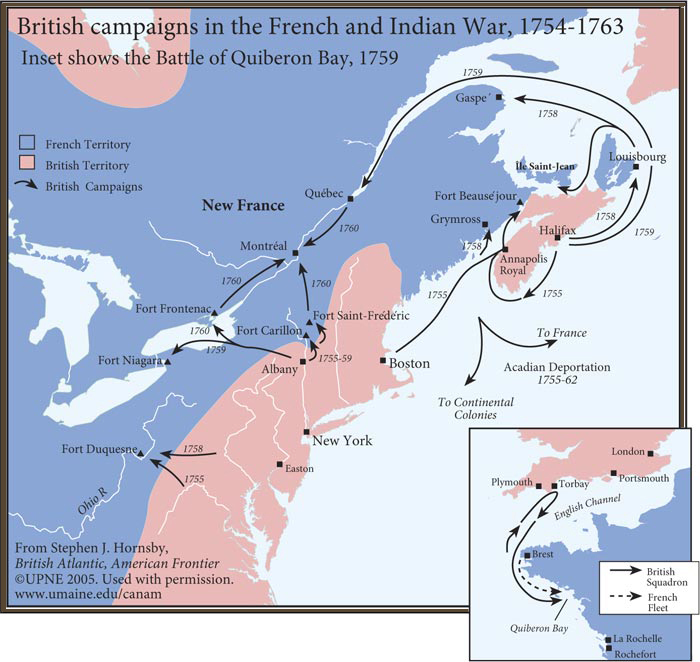

Illustration: Campaigns of the French and Indian War |

|

|||

|

|

Click here for a full size image | |||

Governor Charles Lawrence's Carpe Diem: Decision is Made for the Acadian Deportation

Now with the might and power of the Nova Scotia Council, Nova Scotia Chief Justice Jonathan Belcher, Massachusetts Governor William Shirley, Lieutenant Colonel John Winslow, and Lieutenant Colonel Robert Monckton together with his command of the recently arrived 2,270 British regular and New England militia troups who had recently taken Fort Beauséjour and Fort Gaspereau from the French at his beacon, Governor Charles Lawrence set the course for the ethnic cleansing. Governor Lawrence described his "Great and Noble Scheme" in a letter to England:

"I will propose to them the Oath of Allegiance a last time. If

they refuse, we will have in that refusal a pretext for the

expulsion. If they accept, I will refuse them the Oath, by

applying to them the decree which prohibits from taking

the Oath all persons who have once refused to take it. In

both cases I shall deport them."

After the fall of these garrisons, meetings with Acadian delegates were ordered by the Nova Scotia Council and took place on July 28, 1755. Present at these meetings were Lieutenant Governer Lawrence, Massachusetts Governor, William Shirley, British Admirals, Edward Boscawen and Savage Mostyn, the Acadian delegates, Nova Scotia Chief Justice Jonathan Belcher and the Nova Scotia Council. During these meeting the Acadian delegates were threatened with expulsion from their territories if they did not sign an immediate, unconditional oath of allegiance to the British Crown. The Acadians expressed willingness to sign the oath as they had done in 1730, but only on condition that they would not be required to bear arms against the French.

With word of the Acadians bearing arms at Fort Beauséjour, Governor Lawrence reached a point of intolerance with another refusal by the Acadian delegates to take unconditional oath to the British Crown. Combining this recent refusal with the fact that Acadians had taken up arms against the Crown at Fort Beauséjour, Lawrence ordered Colonel Monckton to expel the Acadians from the Chignecto territory and destroy their settlements. The Acadian die was cast.

Description from "Société Promotion Grand-Pré": the Grand-Pré National Historic Site of Canada Website

On August 19th, 1755, 313 New England troops under the command of Lieutenant Colonel John Winslow disembarked at Grand-Pré and marched to the center of the town. Winslow quickly took possession of the parish church as his base camp and ordered his men to build a palisade for their defense. Winslow then summoned all Acadian men and boys over the age of 10 to come to the church on September 5th to hear a royal proclamation. When they arrived, the 418 unsuspecting Acadians were arrested and informed that their properties had been confiscated and that they and their families were to be deported.

For weeks, the Acadians of Grand-Pré remained prisoners while Winslow waited for the deportation ships to arrive. In October, the first convoy of deportees embarked for the Anglo-American colonies of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland. Due to a lack of vessels, the last Acadian inhabitants of the Grand-Pré region did not embark until December 20th. Winslow's men burned the settlements around Grand-Pré in order to deny shelter to any possible refugees.

Winslow's men deported approximately 2,200 Acadians from the Grand-Pré region. Between 1755 and 1763, British forces deported over 10,000 Acadians from what are now the provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. Others evaded capture by fleeing or going into hiding.

source: Grand-Pré National Historic Site of Canada Website:

Sources: History of Acadia, From Its First Discovery To Its Surrender To England By The Treaty Of Paris; James Hannay; St. John, N. B.: Printed by J. & A. McMillan; 1879

Faragher, John Mack. A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians From Their American Homeland. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2005.

CANADA; By SIR J. G. BOURINOT; K.C.M.G., LL.D., LIT.D.; NEW AND REVISED EDITION, WITH ADDITIONAL CHAPTER BY WILLIAM H. INGRAM, B.A.; T. FISHER UNWIN LTD LONDON: ADELPHI TERRACE; Copyright by T. Fisher Unwin, 1897 (for Great Britain); Copyright by G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1897 (For the United States of America). Title: Canada; Author: J. G. Bourinot; Release Date: September 10, 2007 [EBook #22557]

FRANCIS PARKMAN; MONTCALM AND WOLFE; With a New Introduction by SAMUEL ELIOT MORISON; COLLIER BOOKS; NEW YORK, N.Y. 1884 edition; First Collier Books Edition 1962; Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 62:16974; Copyright (c) 1962 by The Crowell-Collier Publishing Company All Rights Reserved; Title: Montcalm and Wolfe; Author: Francis Parkman; Release Date: December 29, 2004 [EBook #14517]

Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

Grand-Pré National Historic Site of Canada Website:

CHRONICLES OF CANADA; Edited by George M. Wrong and H. H. Langton; In thirty-two volumes; Volume 9; THE ACADIAN EXILES

A Chronicle of the Land of Evangeline; By ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY; TORONTO, 1916; The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Acadian Exiles, by Arthur G. Doughty; #9 in our series Chronicles of Canada; Release Date: September, 2004 [EBook #6502]; Etext produced by Gardner Buchanan.

Note on Gutenberg Project ebooks: The Project Gutenberg EBook of Montcalm and Wolfe, by Francis Parkman; These eBooks is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with these eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net;

http://www.grand-pre.com/Archeologieen.html

yahoo.com

yahoo.com